Home is where the heart is

[This is one of series of blogs to promote my campaign to produce a 30-year retrospective book.]

Maxwell House had been closed for nearly a decade when Leo White and I signed in with the lone security guard and took a tour.

“I moved to the Daily Mirror as northern news editor in 1969 and this place was almost certainly Kemsley House back then,” he says, as we go down into the basement. “Kemsley was the old newspaper dynasty, they owned the Evening Chronicle, the Sunday Chronicle, and the Daily Dispatch. They also had the Sporting Chronicle, and the Formbook.

“By the time I left it had become Thompson House and then Maxwell House. Whilst I was here newspaper production didn’t change at all. We were always doing it the same way until the end, when Maxwell came.

“The press hall looks very different now because the floor above has been taken out. But then it had a low ceiling with the presses in a long line all along here.

“It was incredibly noisy and very busy. The whole building would shake once the presses started. We were three floors up on the editorial floor and you could even feel it there.

“Before my time pony and traps used to clatter down Balloon Yard to Victoria Station. You can imagine the horses coming along here and screeching to a halt. Newspaper drivers always thought they had to get from 0 to 60 in as many seconds as they had fingers. To this day, they still do.

“You felt you were in the big time, especially at night. You’d have lorries backed up here and all the way down those loading bays… you had to perfect the art of getting across the yard without being knocked down.

“We’d come down here from time to time. These were the management offices for the Kemsley or Thompson people, or whoever was in charge.

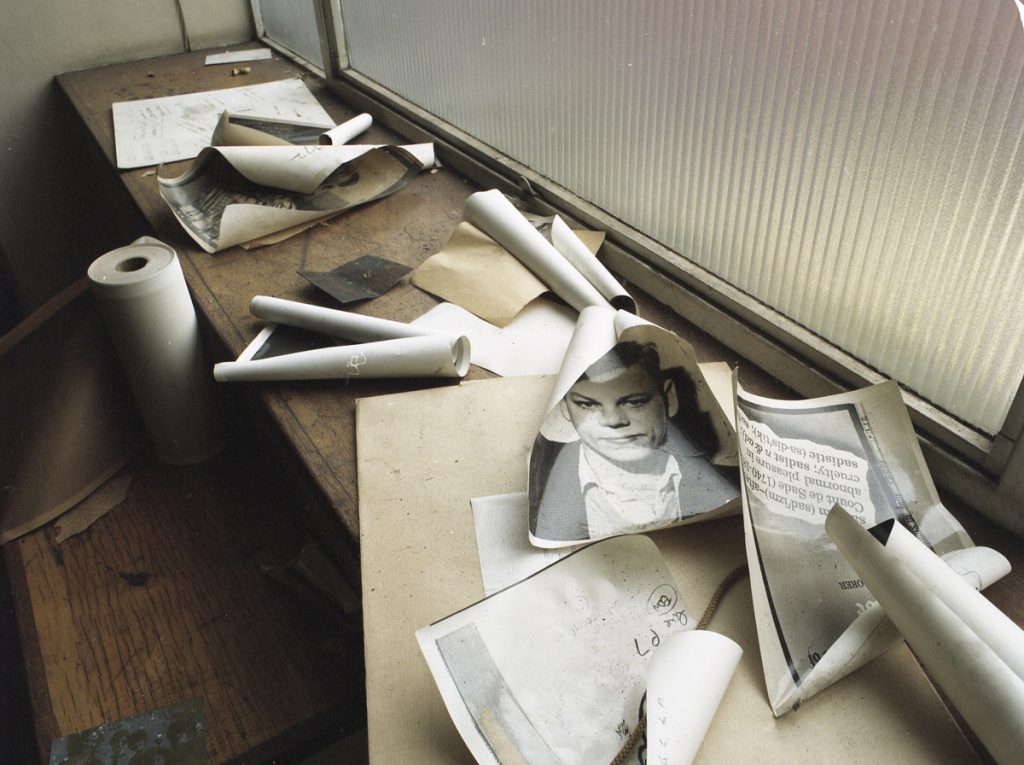

“It was very posh dow here: marble floors, mahogany-panelled walls, decorative glass doors almost from a different age. They had window screens to keep out the traffic noise. The parquet flooring was worth a fortune and beautiful at the time, obviously it’s ruined now. It takes on a totally different look when it stripped out. It’s sad to see it in this state.

“Here we are, home is where the heart is. This was the newsroom, our newsdesk was there. I’d sit here, my deputy opposite me. I’d have an assistant there and the Irish Editor and picture desk would be over there. The reporters’ benches were all along the back.

“That was the editor’s office, and that’s where we’d have our conferences. I’d start work at 9am and finish about 7pm. We’d have the first news conference at about 12.30, a mini one in the afternoon, and then at six we’d have the main conference. Depending on the train times, the first editions to Scotland, for example, would go out at about 9pm.

“We’d watch that clock all day, especially if you were having a tough time. It used to tick, tick, and drop over. It was the focal point of the room really. I’d be watching from my desk, the reporters would be watching it, the chief sub, the night editor, everyone.

“In the newsroom we had guys who were called messengers and we always knew them as messengers although some of the older chaps used to shout ‘boy!’. It was nothing derogatory, it was just something they had always shouted and had never really thought about. Then, in the rebellious mood of the early 70s, the messengers got a bit uppity and thought it was demeaning to be called messenger. So they were re-designated ‘editorial assistants’ which sounded better. If you felt inclined you might then shout ‘editorial assistant!’ and they used to get very uptight about that.

“These posters around the newsroom tell you how many letters you can get to the inch, and how tall the letters will be. This is the number of the type. Instead of having to write ‘tempo bold italic’ you just put 583 x CAP. It was a reference number really. A lot of them we didn’t use.

“Your story would go to ‘lino’ where there’d be row after row of linotype machines all clattering away setting the type in lead lines. Each operator would only get part of the story because his machine would be set up for just one size of type. For instance, you might have the intro in say, 10pt across two columns but the main body of the story would be single columns in 7pt. The lines of lead produced from each of the machines would be collated later on the ‘stone’, like a huge table where all the pages were assembled according to the page layout.

“Withy Grove was like a small town on its own. It was really buzzing. Pubs and nightclubs around here thrived on us. When people finished work they’d go and have a few ‘bevvies’. There was The Swan, Hare and Hounds, John Willie Lees, and the Press Club was just down here on Dantzic Street. We must’ve kept a whole generation of taxi people going. When the place closed down I bet the local economy didn’t half suffer.